Sending Signals: Houses in the Lives and Biographies of a Zambian Alderman, a President’s Spouse, an African Clerk and Many Others

Sending Signals: Houses in the Lives and Biographies of a Zambian Alderman, a President’s Spouse, an African Clerk and Many Others

Kirsten Rüther

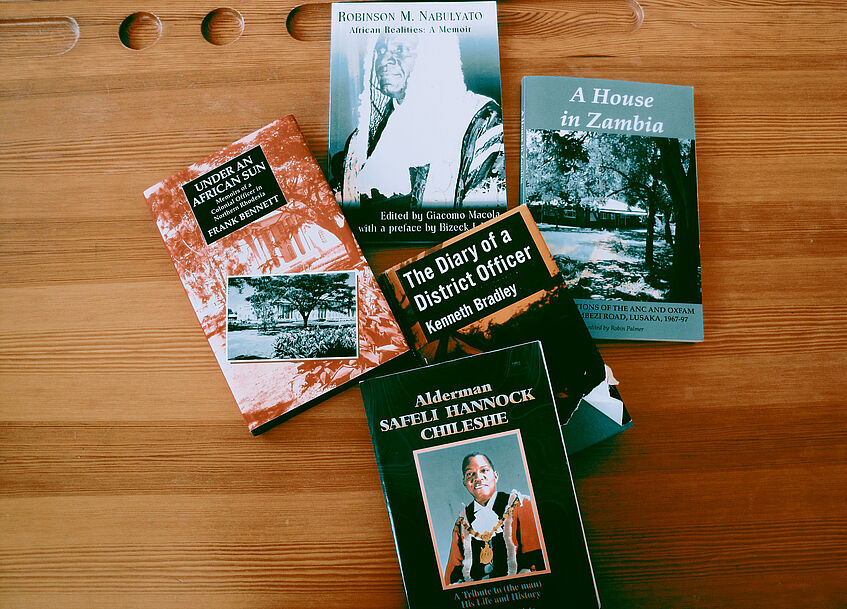

Let’s admit it right away: Many of the texts I am going to talk about are not a great pleasure to read. I am talking of personal narratives, autobiographies and popular biographies, exercises in life writing and even obituaries, partly self-authored and partly written by family members of the next generation, journalists or personal acquaintances of those whose lives are told. Authors of the texts and authors of their lives, the majority emerged through colonialism and independence as crucial builders of, and contributors to, the Zambian nation.

Of course, every life is worth telling. But, honestly speaking, not any narrative rendering of it is enhancing. It also has to be taken into consideration that, more generally, the “biographical” and “autobiographical” genres, these culminations of especially male self-writing in the Northern hemisphere, are not necessarily the preferred expression of the self or one’s life in Zambian surroundings. And yet, the texts I have learnt to appreciate despite their (and perhaps even due to their) shortcomings in literary quality have constituted an extremely important source for understanding varying constructions of personhood as pitted against one’s dreams, one’s hopes and disappointments, and one’s experiences of everyday living circumstances. Moreover, in a substantial number of texts biographers and the biographed persons refer to the dwellings they grew up in, the difficulty of accommodating a family, the technical skills one needs to build a house and a home. This is why in our project on housing in Zambia autobiographies (some of them popular, others more “serious” or academic) and especially popular biography assume crucial importance as sources for historical investigation – perhaps more than literary reading – for a time when archival repositories are either not available or becoming thinner. After all, they capture some “voices” of some individuals who lived through colonialism, its end and its aftermath – irrespective of how tricky the use and interpretations of these texts become for exactly that reason.

I exactly recall how I became attracted to this primary material. I was reading through Jonathan H. Chileshe’s Alderman Safeli Hannock Chileshe: A Tribute to (the man), His Life and History, a biography written about a father and respected Zambian by his eldest son. In this text, descriptions of, and comments on houses proliferated. Already at very first sight, there was a wealth of information and symbolism in the way housing ran through this text like a meandering red thread. Safeli Chileshe’s father, the biographer’s grandfather, was a bricklayer, who had learnt his skill from Catholic missionaries. He later worked for various construction companies and the Public Works Department. In this capacity he not only erected the David Livingstone statue facing Zimbabwe but also constructed the very steps that in 1947 the British Royal family used for disembarking from the Flying Boat on their visit to the territory. This bricklayer family owned a plot and a house in the Malota compound of Maramba, Livingstone, and lived in humble wealth. I was so fascinated to see how here a family genealogy was set up which, in terms of representation in writing, laid claim to having had a stake in building the country from very early on.

There was more on housing, building the nation and pursuing an aspiration to participate in the country’s politics and administration. Unable to pursue his father’s career (as at that time artisan work was reserved for poor and illiterate whites and coloured people), Safeli Chileshe managed to become a clerk. A bursary took him to England for further training, while his wife and five children stayed behind at Kabwe. After his return, housing allocation became an issue. Chileshe remembers that in Lusaka teachers’ houses were often sited on the western side of camps, adjacent to student dormitories, and at quite some distance from white teacher colleagues. As Chileshe was now to take up a better job in the Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland Publication Bureau, it was not immediately evident for the authorities where to put up the family without “sending a wrong signal to either whites or Africans”. Neither a house in the midst of whites nor accommodation in Matero, Old Chilenje or New Chilenje African compounds seemed appropriate. Therefore, houses were hurriedly constructed on the western side of Burma Road – for the Chileshe, Mumbuna and Chellah families. Safeli’s house faced the back of some white artisans’ houses on corner Ash Road/Burma Road in Woodslands. Chileshe recalled it all with absolute precision: The road, located on the edge of Chilenje Senior Primary School, worked as a dividing line between the African “compound” on the West and some artisan Europeans on the East. Chileshe found himself adjacent to some houses built of concrete blocks for Africans who were considered slightly better off than the rest of Africans who occupied quarters in the main Chilenje compound. Chileshe now lived in a “no-man’s land house”, as he recalled.

When at a later stage in his life Chileshe resigned from the civil service his family moved to Lusaka West End, popularly known as Chinika. As his biographer states, perhaps from lore running in the family, “He could not have moved into the European residential areas because the white residents would have raised the type of protest that the administration would have been unable to handle. In other words, there was no visible liberal white administrator who was willing to risk his or her neck for the sake of satisfying Safeli Chileshe’s short term interests.” I love this remark! It conveys such a great amount of wit and self-confidence with so much lightness that I still like to re-read this outstandingly brilliant comment. With great love of detail Jonathan Chileshe, the son of the alderman Chileshe and the grandson of the bricklayer, describes the materials of which his father’s houses were built. The family sometimes lived in two small rooms of sun-baked bricks, grass-thatched roofs; in Kamwala and Old Kabwata, they occupied a single room amongst round huts, where water was provided through communal standpipe at some central place. In Ngwerero Road in Roma township Safeli Chileshe finally attempted to “replicate a monstrosity of a house he had seen and admired whilst on a visit to the US.” This ambitious project was never completed. Instead, the Zambia State Insurance Company, which had lent Chileshe the money eventually, repossessed the incomplete structure.

There are many more details about the houses in which Safeli Chileshe lived and how, in addition to his profession and honorary positions in advising committees and governing bodies, he time and again committed himself to some building projects. It is probably quite clear to see why Chileshe’s biography triggered my curiosity whether there would be other biographies and autobiographies talking about housing in similar vein.

And, in fact, there are. More interesting even, others refer to houses and housing in different ways. Betty Kaunda, for instance, who narrated her biography to Stephan A. Mpashi, her biographer, mentions that when her husband took her to Lusaka, “There was no house for me and the children, so we had to live in the Congress office.” Her reminiscence draws attention to the fact that housing is not only an expression of social aspiration, but that it becomes a particular concern once it is not available. “In 1954, a house was found for us in the Mapoloto section of Chilenje. It had a cement floor, three rooms and detached kitchen, the roof was made of grass. There were no chairs in this house but there was one small table which we used for meals. The trouble with this house was the rain. Rain came through the grass roof and everything in the house became wet. I had a lot of work cleaning the rain water from the floor. Sometimes rain came again immediately after I had finished the operation. The worst times were when it rained during the night. My husband and I would wake up and pile all our blankets on the bodies of our sleeping children, then we would find a safe corner and stand there the whole night through.” Her description goes even further, revealing the difference in emphasis – and perhaps in experience – as compared to the Chileshe biography.

The further one digs into these and additional texts and the more one comes across repetitions of themes and experiences, the clearer some social and historical structures and processes become. There were others whose fathers worked for construction companies. Simon Kapotwe’s father, for instance, learnt carpentry at a Mr. Turner’s carpentry shop where he qualified as a cabinet maker. He later went “to the Belgian Congo where many people of his trade had gone and had returned with shiny bicycles, double terai hats, squeaking shoes and many francs in their pockets. Turner-trained cabinet-makers had a reputation of being capable of turning out good furniture and of being good workers generally. They earned good wages wherever they went and very often worked their way up quite rapidly.” I take this as a first hint at some kind of a “founding profession” which a number of biographers considered worthwhile mentioning about their parents or grandparents. Could it be that having had a properly trained artisan in previous generations represented an alternative basis for claiming a family’s respectability and their participation in the building of the then colonised and later independent Zambian nation? Could the claim to descent from artisans represent an alternative narrative of social upward mobility and ascendency into political office as compared to the more familiar ones of having had access to education through missions? That is something I still have to draw out from further reading.

Other biographed persons, such as Kenneth Kaunda, in union with their biographers depicted the houses in which the family lived as a haven from strife, as a middle-class home full of books and a place for learning. “Today, with his own large family, singing to the accompaniment of the guitar is still a favourite pastime when Kaunda can escape for an evening from the responsibilities that beset him. In 1961 a distinguished British journalist was bearing news of an important development on which he wanted Kaunda’s comments. The visitor paused at the door of the tiny ‘location’ house and heard from within the sound of ‘The Lord is My Shepherd’ being sung in Chibemba. The Kaundas were sitting in their living-room by the light of a candle, and the man whose name was making headlines around the world alongside those of Welensky and Macleod was calmly strumming his guitar.” Again – what a paragraph!, entangling “Africanness” and Christianity, nationalist politics and family romance, the work and voice of a journalist, a politician and the Lord!

Others, yet again, recall how they - at least in the initial stages of their teaching careers - shared accommodation: “So Alport and I coexisted happily under one roof for five months before I moved out to go to Munali.” This, again, is more than just a minor statement, especially when read against the recurring complaints one finds in archival files that Zambian families in the late colonial period did actually not like detached houses where two families lived under one roof, had to compromise with regard to their privacy.

Needless to say that biographies such as these have gained my interest. I have become keen on finding out how the many details add up to a focus through which to assess experiences of living through colonialism and the days of independence. I have become keen on finding out more about how experiences and narrations of housing tell us something about how the spheres of the private, the political, the everyday and the personal intersected. And last, but not least: Anyone reading this blog and knowing of further biographical and autobiographical texts, please contact me and share your knowledge with me!

Quotes taken from:

Jonathan H. Chileshe: Alderman Safeli Hannock Chileshe. A Tribute to (the Man), his Life, and History. Ndola: Mission Press, 1998.

E. S. Kapotwe: The African Clerk. Lusaka: neczam, 1980.

Stephan A. Mpashi: Betty Kaunda. Lusaka: Longmans, 1969.

John M. Mwanakatwe: Teacher, Politician, Lawyer. My Autobiography. Lusaka: Bookworld Publishers, 2003.

January, 2019