What cue in Kew

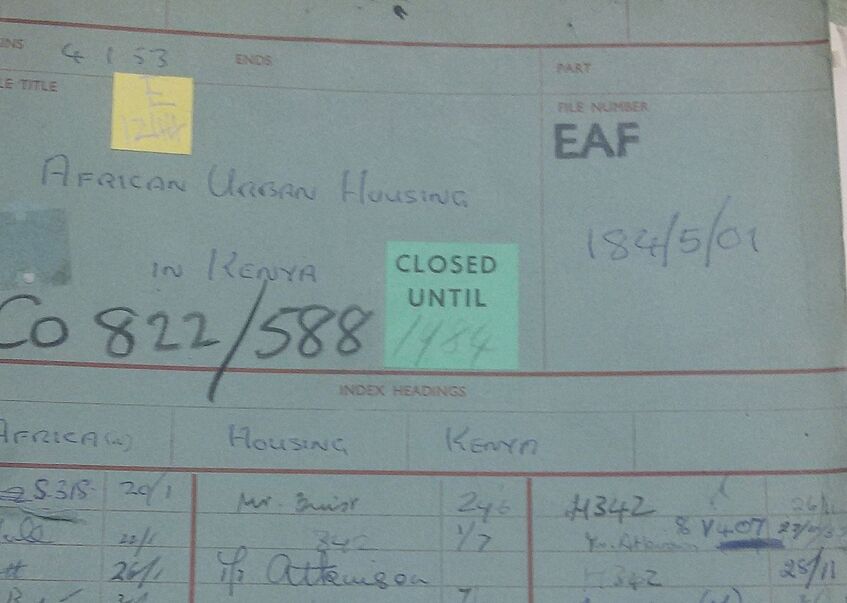

Colonial Office File on African Urban Housing in Kenya, 1953 @Martina Barker-Ciganikova

What cue in Kew

Martina Barker-Ciganikova

What cue the British National Archives in Kew gives about housing in Africa

That housing in the colonies was an important topic for the British Colonial Office (CO) is evidenced by the amount and the detail of the records available in the National Archives situated in Kew. Not all aspects of housing, though, were covered evenly, depending on who was talking, when and where. At times, the debates converged or complemented each other; at times a researcher into housing matters must wonder if we are still talking about the same thing when talking about housing. Fascinated by the multifacetedness of the concept while ferreting through the records, I identified distinctive ways of how one talks or does not talk about housing by putting certain aspects into the spotlight while silencing others.

While I found an overwhelming amount of data on Nairobi and Mombasa (my research focuses on Kenya), I gathered surprisingly little on “secondary towns” or rural areas. Rich information on mobility, circulation and exchange of ideas, concepts, and experts - in particular through housing conferences, implementation of city master plans, or appointments of town planning advisers - was also available. On the other hand, data on gender and the role of women in/for housing was scarce. So were the voices of those to be housed.

No other aspect was as prevalent as that of finance (or rather, the perpetual lack of it). Every file that passed through my hands referred, in one way or another, to the financial mechanisms provided by the Colonial and Development Welfare Act or the Colonial Development Corporation. Other, often municipal, funding schemes and loans were given equal attention. Memos, minutes, dispatches, and communications passed from one office to another counting and recounting the disposable funds, and again and again ascertaining that what is available is not enough. Building material was the next on the list. The technical details of what to use where, when, for whom and most importantly how much? Corrugated iron or mud and wattle? Stone or cement? Imported or local? Only seldom was there a univocal answer to any of these questions.

What drew my attention particularly strongly was the organizational structure of institutions and experts dealing with housing and how they communicated with each other. Housing was seen as a crosscutting issue with implications for a range of social, political, economic and cultural developments. In fact, several of the records mention “the indivisibility of the problem of housing”.

As the complexity of the tasks was growing, so was the vastness of the network dealing with housing. New specialized actors began to emerge both in London and in the colonies. Beside the various departments and sub-departments, a large number of advisory committees and specialized advisors, including a special adviser on housing issues to the Secretary of State, Mr George Atkinson, were called into life. My confusion on who is who drove me to attempt to create a network of those who played a pertinent role in housing. I started with the Colonial Office, within which housing was situated under the Social Services Department. So far so good. But then there was also the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research harbouring the Building Research Station and the Tropical Building Section, the Colonial Housing Research Study Group, the Colonial Research Committee, - and the Housing Advisory Committee set up with the sole purpose of advising on the setting up of another body – the Colonial Housing Research Bureau. Plus the advisory Panel in the field of Town Planning, Housing and Architecture and The Managing Committee of the Bureau of Hygiene and Tropical Disease, and…my organigram never got finished.

The communication between these various actors and echelons of the colonial government constituted the bulk of the archival records. Its analysis reveals that the planning of housing was highly bureaucratic and centralized with insufficient exchange of information between the metropole and the colony. The procedures were lengthy and time consuming; the decision-making, even for rather minor issues such as appointment of Town Planning Advisers, was marked by internal conflicts and might take years to conclude. The institutions were ill prepared and, though working simultaneously, they were poorly coordinated. The multiplicity of actors stood in contrast with the constant lack of qualified personnel.

The mismatch appeared very striking and somehow illogical to me. Despite the widespread acknowledgment that housing (and town planning) should have upmost priority within the colonial administration, there was a constant shortage of houses and, if they were made available, the conditions were either deplorable or non-affordable to the majority of the workers and most of the low-income households. The planning failed. Something went wrong along the way.

I could not put my finger on it. Was it the lack of finance, building material and professional personnel (in particular during the war years)? Or was the fact that housing was treated as a technical matter, a depersonalized and a depoliticized one, as if one universal (but intrinsically British) solution was applicable in all colonies, to blame? Could it have been because housing was rather a means to achieve other ends such as sanitation, productivity, control, or pacification than an end in itself? Or was it in the end the lack of political will to implement the resolutions? Most certainly a combination of these.

The records in Kew represent only part of the answer, the official mind: technical and financial matters, building materials, organizational structure. That is one possible way to talk about housing. It remains, however, incomplete. It reveals only very little about what housing meant to its recipients, what type of building materials they desired, or if communal washing facilities were their preferred choice, etc. To complement these voices and fill in the gaps, my next research stay takes me to the Kenyan National Archives in Nairobi.

Februar, 2018