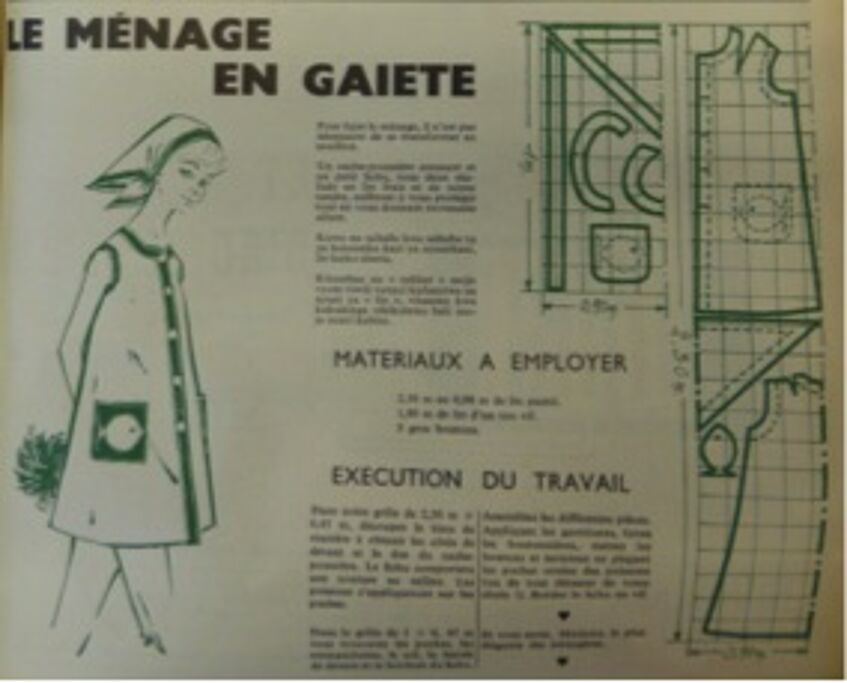

Edition of Mwana Shaba, No. 10, Oct. 1965, p. 19 dedicated to 'cleaning in style'. @Daniela Waldburger

"Votre page madame"

Daniela Waldburger

"Votre page madame" - Cleaning in style in Elisabethville

After its foundation in 1906, one of the most important players of interest in the mining sector in Katanga was the Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK). Especially after in the 1930s the International Labour Organization (ILO) lobby put pressure on the UMHK to abandon forced work, the UMHK had to search for a solution to secure its high demand for a permanent workforce so that workers would sign up for long-term contracts. The company’s strategy was a huge project of social engineering, including the development of a new employment policy called ‘stabilisation’[1]. In 1925 the UMHK founded a department to control and organize these projects (Departement Main d’Oeuvre Indigène). Besides the provision of schools, hospitals, leisure facilities and, of course, housing, the Belgians also pursued their continuous endeavour of ensuring cleanliness and hygiene[2]. The house became one of the core objects of social engineering. It reproduced the Belgians’ ideas on family and home in every sense, ranging from the ideal size of a family via the ideal interior to the distribution of duties within the household. I was intrigued by the preoccupation of the UMHK and Belgian colonizers with hygiene, may it be on the higher (organizational) level (different neighbourhoods for different city dwellers) or on the lower level of hygiene within a neighbourhood or even the house.

During my recent research stay in Brussels in February 2018 I went through thousands of pages of minutes of the UMHK’s different committees, such as the Board of Directors in Brussels to the Board of the Human Resource Department of the UMHK Services d’Afrique in Elisabethville (later Lubumbashi), from UMHK’s medical reports to minutes by the Companie Foncière du Katanga (Cofoka), UMHK’s real estate company in the Congo. Surprisingly little referred explicitly to the UMHK’s concern with hygiene. Implicitly, however, many hints towards the achievement of it could be found. I indeed came across one of the most unexpected insight into UMHKs’ efforts to control hygiene in Mwana Shaba. Mwana Shaba (and Mwana Shaba Junior for the youth) is the UMHK’s and it’s following corporate bodies’[3] house journal. Mwana Shaba is the Swahili term to describe a copper worker and, as the journal’s name indicates, the potential readers were the workers of UMHK’s copper mines. The Annual Rapport of 1956 of the Services d’Afrique, Department M.O.I. described the incipient journal as follows: “Mwana Shaba qui est rédigé en français et en kiswahili paraît tous les mois; plusieurs années. Le Journal d’Entreprise est déstiné aux 27.500 travailleurs de la Société et de ses Filiales. […]” (p. 44) It was further mentioned that Mwana Shaba would present articles of general interest for the “indigenous” staff (personnel autochtone) (p.44.), information of the Company, and – all in all – wouldcontain educative articles on different topics. Among the diverse (and many educative) sections of Mwana Shaba the section dedicated to the women, “Votre page madame” (Your page madam) drew my attention. Across a huge section of “civilizing” ideas such as hairstyles or recipes for the loving husband, the reader (in this case the woman) is confronted with the ideal appearance and social behaviour, and many of these civilizing aspects are linked – in one way or another – to the UMHK’s idea of hygiene, from proper nails for proper women to the proper way of childcare. In the following I would like to point to two examples of explicit references to hygiene in Mwana Shaba, both from 1965.

The first example refers to the big cleaning of the house (le grand nettoyage) which was published in the first issue of Mwana Shaba in 1965. In a highly detailed manner every step of a big cleaning is described. Readers learnt, for instance, that the woman was expected tomake use of a wet cleaning rag, how to scrub the clothes and many more details. As a term, however, “the big cleaning” also refers to general suggestions. It was deemed inappropriate if children slept in dirty clothes. They were supposed to be clean andto sleep in a clean bed (Il faut que l’enfant soit propre pour s’endormir dans un lit propre.) Moreover, it was explained that insects would not enter into a house in which they were strictly dispelled. The article ended with the notification that UMHK’s service d’hygiène would regularly enter the house to disinfect the rooms. Insects, more particularly those mosquitos passing on malaria, represented not only a threat to an individual’s health, but constituted a major threat to the productivity of a UMHK worker. As a result, measures to ensure hygiene were articulated with reference to instructions of the cleaning of the house itself, toways of keeping the house and its dwellers clean and guidelines of how to avoid health risks from outside.

The cleaning of the house was thus presented as the place where hygiene was ensuring the worker’s health and productivity and it was the worker’s wife which was assigned to this responsible position of this civilizing measure. The text is verbalised in the first-person perspective, thus realizing an advice from woman to woman, as the text was mainly addressed to the reader in direct speech, e.g. “You should leave all the furniture in the interior of the house” (Vous devez laisser tout votre mobilier à l’intérieur de la maison). Direct speech creates proximity between the voice of the narrator and the reader, and thus facilitated the transmission of the instructions by the UMHK.

The same strategy to create proximity to the reader was used in the second example, published in the October issue of the same year. It dealt withthe sewing pattern of a cleaning dress, again in the section “Votre page madame”. The reader was again directly addressed, e.g. in the concluding sentence “And you and you will be, Madame, the most elegant housewife” (Et vous serez, Madame, la plus élégante des ménagères). The introductory text was written in French and Swahili. In the minutes of the meetings of Department of the UMHK Service d’Afrique, it was stated that French and Swahili should be used for Mwana Shaba as Swahili was to ensure that the workers would understand the meaning, while French should be used to gradually lead to the enhancement of workers’ command of French. In this brief article the main message was made available bilingually. In the introduction it was explicitly declared that doing the cleaning did not mean that the woman had to transform into a slob (souillon). Instead, wearing the proposed cleaning gown would give her a lovely appearance (ravissante allure). This suggestion was followed by the list of material needed as well as by the manual of how to sew this dress. Two roles were accorded to the woman in this article. Firstly, and like in the first example, she was the one responsible for the cleaning (and again, hygiene). Otherwise the cleaning dress would not have been a topic at all. Secondly, she was expected to fulfil this duty in a style that matched the desired appearance. Her look also mattered, at least in the perception of the UMHK. It seems that nothing must keep a woman from cleaning “in style”. Again, like in the first example, it was the worker’s wife who was responsible for a clean house and thus a hygienic environment. Hygiene was essential to the health of a worker and had to be well taken care of to make sure that his productivity would persist. The title of this article “The joyfulness of housekeeping” (Le ménage en gaieté) thus “sold” the UMHK’s concern for hygiene under the umbrella of an attractive activity. The activities included were first of all the sewing of the dress, an activity that was usually carried out in the social institutions (foyers sociales) and an activity where women were getting together. The second activity, doing the housework itself, was presented to be a chance to be “the most elegant housewife”, at least if the woman would wear the suggested dress.

August, 2018

[1] See e.g.

Seibert, Julia. 2016. In die globale Wirtschaft gezwungen – Arbeit und kolonialer Kapitalismus im Kongo (1885-1960). Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Tödt, Daniel. 2012. “Les Noirs Perfectionnées”: Cultural Embourgeoisement in Belgian Congo during the 1940s and 1950s. In: Working Papers des Sonderforschungsbereiches 640, 4, edoc.hu-berlin.de/series/sfb-640-papers/2012-4/PDF/4.pdf

[2] The whole city of Elisabethville was organized around the idea of securing hygiene. e.g. the definition of zones, public housing estates, “agglomerations congolaises”, rights to property, rights to the city, etc.

[3]Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, 1957 -15 February 1967; Gécomin, 15th April 1967-15th May 1970; Gécomines, 15th June 1970 – 15th November 1971; Gécamines, 15th December. 1971-1991.